This is an evergreen note that I will be revisit regularly to develop a comprehensive list of note-taking approaches including their practical implementations in various software tools. This post will serve as an elaborate table of contents, including a brief introductory discussion on the importance of note-taking, followed by a high-level walkthrough of each method. Links to posts and videos with detailed examples and descriptions will follow over the coming weeks and months.

Table of contents

- Introduction

- Meeting notes

- Application design

- Lecture and conference notes

- Reading notes

- Personal notes (Journaling)

- Checklists

- Fleeting notes

Introduction

Why the fuss about taking notes?

Writing is thinking. Taking notes is writing.

Think is important because action you take based on thinking will be more productive than action based on ignorance. If you learn to think through writing, then you will develop a well-organized, efficient mind. (Dr. Jordan B. Peterson)

By synthesizing the information you come across during the day, into a set of useful notes, you engage your mind at a deeper level, beyond simple understanding. Taking quality notes will not only help you remember what was said, what you have read or who has what action, but will also sharpen your thinking and improve your decisions and actions.

We cannot manipulate many ideas in our minds at the same time. It is simply the case that we can only operate with a maximum five to ten thoughts in our minds at the same time. The good news is, you can write down much more than you could ever hold in memory. Thus, you have an efficient way to work around the limitation of your ability to process information. Through writing, you build the capacity to consider a higher number of ideas at the same time. When you put ideas into writing, you develop power over them. You can move them around, change them, discard them, analyze them word by word, sentence by sentence, paragraph by paragraph.

Note-taking is a critical skill not just in school, and just at work, but a critical in all of life.

Note-taking workflow

I assume that you aim to only attend meetings and conferences, read articles and books, that create value in your life. Apart from the rare example, I believe that you always have a choice. To "vote with your feet", to skip the events and books that are genuinely irrelevant or do not create value for you.

With this assumption of free choice and value creation in mind, the fundamental question to ask yourself is whether you want to be busy or productive. Often, we engage in meetings, read books, attend conferences rushing from one to the next, without putting in the effort to drive value from our time investment. This seems foolish considering all the trouble we go through to organize and attend meetings, or to free up time to read a book, etc.

Notes serve multiple purposes. Even if you never user your notes again, the act of taking notes will improve your thinking and contribution. Design your notes with the following two considerations in mind.

- Findability. When will you want to find this note, and how will you search for it? File notes based on likely search terms you will use in the future, not based on topical tags that you would use in a library.

- Notes finding you. Consider when in the future would you want to stumble upon your old notes. Often we do not even remember to search for our old notes. We don't even remember we have those notes. Your note taking system should be design such that old notes find you at the right time, instead of you having to remember to look for them.

Effective note-taking starts before you begin the meeting, or engage in reading, and end after you have put the book down, or left the conference room.

Before: preparation

As a first step, reflect on the following questions.

- What is the purpose of the meeting? Why are you planning to read the book or article? What is your purpose with personal journaling?

- What questions would you like to get answered?

- What decision are you seeking?

- What do you want to learn?

- What form of note-taking will best serve your purpose?

If the meeting has pre-reads, take the time to familiarize yourself with it. It is not always necessary to read all the pre-read word for word, but it is important that you are familiar with the material and you make a deliberate choice based on an understanding, and do not just forget or neglect the pre-read out of ignorance.

You have completed preparations when you have selected the approach and have prepared your templates for taking notes.

During: taking notes

The approach you follow as you take notes will vary depending on the method you have selected. Your aim should very rarely be to record conversations verbatim or to copy long stretches of quotes from text you are reading. Instead, you need to adopt a mindset of searching for the key statements, decisions, actions, etc. informed by your aim and the questions you want to answer, or the decisions you seek to land.

After: review, summarization, distribution

Depending on the type of notes, there are different time horizons for "after".

In case of meetings, "after" usually means immediately after. It is best practice to schedule 15 minutes after each of your meetings to clean up your notes, and in best case to distribute minutes and actions.

In case of reading a book, "after" could mean the weeks after you have finished the book. Follow up could include writing a short abstract or summary focusing on key reflections, questions, and learnings from the book.

Organizing your notes

The reason for keeping your notes tidy is to help your future self find relevant information. Note-taking systems typically include multiple means to organize information. One common feature of these is how easily they get out of hand.

It is not possible to build a perfect system on the first attempt. Your organizational system will evolve as you come across additional information and real-life questions. Each time, you will innovate and extend your system.

In Keeping Your Notes Tidy - How do You Manage the Growing Number of Tags? I share two examples. One that I have matured and used in TheBrain for close to eighteen years. The other, my approach in Roam, is relatively new.

In Organizing Your Notes in Roam - Understanding Pages, Blocks, Tags, and Outlining I discuss fundamental strategies for organizing information for findability.

Meeting notes

By taking the effort to record and distribute meeting notes, you increase your influence and power within your group. Having written the minutes, you will own the narrative for the meeting, the one people will remember. If you want to be noticed and rise through the ranks, take notes in every meeting, compile those notes, and distribute to attendees with action items and next steps highlighted. (Chris Sacca)

One-on-one meetings

I have a detailed post on taking notes in One-on-One Meetings.

One-on-one meetings are typically reoccurring conversations focused on progress tracking and/or coaching and relationship management. The agenda for these meetings is usually slowly evolving, each meeting building on the outcome of the previous. One-on-ones are held with employees, key stakeholders, key customers, etc.

When executed well, one-on-ones can significantly boost team productivity, morale, and engagement.

Committees and Decision Review Boards

Best practices:

Board Meetings

Team meetings

Team meetings include project meetings, working group meetings, departmental meetings, and more. Your goal is to solve a problem or progress a topic. Team meetings should always have an owner who sets the agenda and takes care of maintaining minutes of meetings. Even if someone else is managing minutes of meetings, you will still benefit from capturing your own notes.

Quadrants Method

One effective approach for taking notes in team meetings is attributed to Bill Gates. (Grokable, Post BillG Review)

Split the sheet into four quadrants.

- Questions: Write questions that come up before or during the meeting. Make sure you get answers to these before leaving.

- Notes: Record key thoughts, arguments, decisions, but also anything that comes to mind during the meeting. These could be reflections or thoughts that pop into your mind during the meeting.

- Personal to-dos: What actions are you taking away from the meeting?

- Assign to others: Note down information that you need to pass onto others or actions you need to delegate.

Shared notes

Ad hoc meetings

Imagine the situation you are eating lunch with your boss in the company cafeteria and one of your boss' important customers joins you unexpectedly at the table. You discuss pleasantries, talk about holidays, family, and the weather, but in-between these niceties this customer shares a request or an idea with your boss. Later that afternoon, your boss casually approaches you and says, "Remember our discussion with ... during lunch. Could I ask you to follow up on his idea?". You would probably feel uncomfortable if you simply blanked on the conversation and had to say something like: "I am sorry, but I can't recall what ... was asking for. Could you remind me please?"

Application design

Reading notes

There are two fundamental reasons for reading. You read for entertainment and for learning. You may take notes in both cases, however, if your goal is to learn or research, then effective note taking is a must.

Zettelkasten

The zettelkasten (German for "slip-box") method was perfected as a thinking and writing system by Niklas Luhmann, a German sociologist. Luhmann, using his system over a career of 30 years, has authored over 70 books and 400 scholarly articles, and built up a collection of some 90 000 index cards for his research.

In the zettelkasten system, individual notes are recorded on index cards. Luhmann used three types of cards and had two slip-boxes.

The slip-box for bibliographical information contained his references cards with a bibliographical data on one side of each card and brief notes on the content of the literature on the other.

The other slip-box contained the ideas he collected and generated in response to what he was reading. This slip-box housed permanent-note cards and index cards. Cards were numbered hierarchically following a system of numbers and letters (e.g., the note about causality and systems theory carried the number 21/3d7a7). Cards at a level of the hierarchy were numbered in sequence, where each card in the sequence represented an evolution of the concept or idea. Whenever Luhmann wanted to branch a concept into sub-topics, he added a next level to the hierarchy. Besides placing cards in sequence, Luhmann also included references to relevant cards in other parts of the slip-box using this numbering system. Finally, index cards served as entry points into the system, listing reference numbers for key permanent-note cards on a topic.

Permanent-note cards did not just contain quotes from the literature he was reading, but were expressed in Luhmann's own voice, translating the idea from the book, to the context where he was filing the note to, written in full sentences, much resembling the quality of his writing in books and scholarly articles.

Sönke Ahrens' book How to Take Smart Notes is a must read about the practical implementation of the slip-box approach.

Progressive Summarization

Tiago Forte defines 5 layers of summarization, each layer simple to implement, and requiring limited effort. By building the layers one on top of the other, the result is a powerful compression of the text. The beauty of the approach is that it maintains context throughout the process allowing for later drill down into your literature notes or even the book if required.

Read my full article about Progressive Summarization and how I automate the process in Roam Research to learn more.

Chapter abstracts

In this approach, when you reach the end of a chapter, you pause for few minutes to author one or two paragraphs of text summarizing your understanding and reflections on the key concepts discussed in the previous chapter. Beyond the two paragraphs, it is also a good practice to articulate questions that come to mind, for which you will seek answers in the upcoming chapters, or that you want to research beyond the book.

You may need to apply some flexibility to the definition of "chapter", as depending on authors, chapters, sections, parts, books, etc. may vary in length. Your aim should be to condense about fifteen to thirty pages into one or two paragraphs. The act of creating these summaries will help you verify your understanding and sharpen your focus for the upcoming chapters.

Sketch-note the book

Doug Neill in his video, How to Sketch-note a Book, outlines a four-step process:

- Read the book. As you read, underline passages that stand out to you and take notes on the margins. The goal is to be an active reader. Through this process, you should capture key ideas and connections to other books and concepts.

- Create rough-draft single-page chapter summaries. Visualize your notes with icons, scenes involving a human doing something, and occasional diagrams such as a flowchart or mind-map.

- Review your single-page chapter summaries and highlight actionable ideas such as good single-idea sketches, to-do items, or future project opportunities. Look to answer the question: "What next?". What do you want to do with that idea?

- Create the single page sketch-note summary of the book. Two important questions to consider are: What is the overall structure? and What details are essential?

I recommend watching Doug's video here.

Lecture and conference notes

Lecture notes and conference notes differ from meeting notes in two important ways. Often your purpose to take part in lectures is to study a subject and to take notes that will aid you in the preparation for a future exam. Also, lectures and conferences are usually less interactive than smaller meetings, offering you more space to take notes as you listen to the presenter.

Cornell Method

The Cornell method is a systematic approach for taking notes during lectures. This approach avoids the need for laborious re-writing of notes.

Your page is divided into three regions.

- Note-Taking Area: Notes are written here during the lecture. Record the concepts fully and meaningfully. Revisit this area after the lecture to complete sentences and to clean up.

- Cue Column: Revisit your notes as soon as possible after the lecture. Write very concise cues here, such as keywords or key concepts, that you will use during reciting, reviewing, and reflecting.

- Page Summary: Write a one or two-sentence summary of the page in your own words after the lecture.

Outlining

This is probably the most common and familiar form of note-taking. The outlining method organizes information in a numbered or bulleted list. Details are indented under summary statements. The bullet point hierarchy can be as many levels deep as practical.

The relationship between different parts is represented through the hierarchy of indentations. Higher level headlines are less indented. Bullet points, numbers, letters, Roman numbers can equally be used at various levels of the hierarchy. From a practicality point of view, maintaining a complex system of numbers, letters, and Roman numbers in real-time note-taking situations is difficult.

It is good practice to leave space between sub-heads as you go, since the presenter may circle back to a topic (or you may have questions or new ideas you want to record), and you will want to have space to add information without making your list sloppy or confusing.

You can also create headings for things like action items, to-dos, and other important information, so you can have an actionable list to refer to later on.

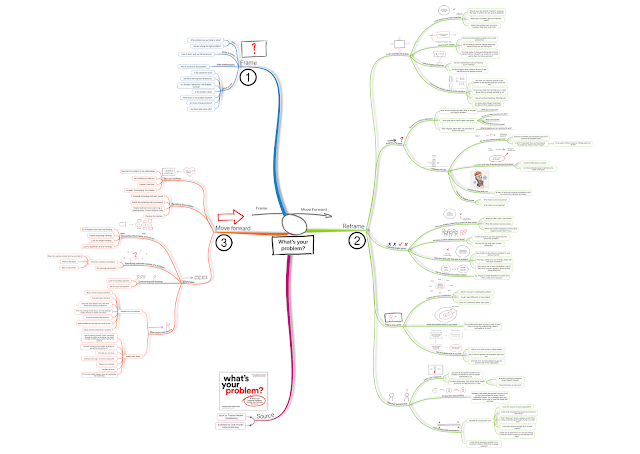

Mind-mapping

At its core, mind-mapping is like the outlining method, with three important distinctions.

You can easily extend the mind-map hierarchy any time during the lecture, this provides significantly more flexibility during note-taking to accommodate additional emerging detail.

The spatial organization of the mind-map helps with retention of the information.

A mind-map may include pictograms and cross-links between different parts, providing additional contextual information.

I have a related post on The Infinite Whiteboard - Visual Thinking with Miro, which I highly recommend if you are interested in mind-mapping and visual note-taking tools.

Sketch-notes

At a conference or university, you will move between sessions and have only a backpack to carry your stuff around. It's best to keep your materials simple. Use a notebook and a single pen, or maybe just a few pens.

Enter the lecture with a rough idea of how you will want to capture notes on the page. In the video below Doug explains that he likes to leave the left page blank, and only sketch on the right side of his notebook. He also has two imaginary columns on the right, which helps him place sketches and text efficiently. He captures a single idea per row and sometimes combines the two columns for a more prominent single idea. He takes a simple top-to-bottom approach for filling his pages.

Taking sketch-notes real-time will not leave you time for complex visuals. Concentrate on the lecture and create simple sketches. You can revisit your notes after the lecture if you want to make them look prettier.

Sketch-noting should focus on capturing key concepts, and everything that was said in the session. It is often helpful to pause note-taking for periods of time and simply listen to the lecture. This will help you understand overarching thoughts which you can translate into sketches of key ideas.

I have a blogpost Showcasing Excalidraw and its integration into Roam Research. Excalidraw is an awesome drawing tool that also allows collaborative sketching.

Charting

If the lecture or presentation is organized around a specific attribute like chronology and the presenter covers information around fixed categories, then notes can be captured in a table format. This approach helps keep track of important details being presented about each entry in the table. It provides a clear structure to follow during the lecture.

Determine the categories to be covered in the lecture. Set up the table in advance, with the categories in the header of the table. Fill out the table cells during the lecture.

The charting method is ideal when large number of facts are presented fast. Use this approach when the lecture is content heavy.

Sentence Method

The sentence method is a linear recording of the lecture organized around individual sentences. Number each sentence and start in a new line. You can use the line numbering for cross referencing as you write.

The sentence method results in somewhat more organized notes as compared to writing in paragraphs. This approach is mechanical and requires only limited additional thinking during note taking.

As you study and review, use a highlighter to add a layer of structure to your notes by bringing out key points. Using multiple highlighters, you can also mark major and minor points.

Writing on slides

This approach is best applied when pre-read is distributed in advance. You can also apply this approach by taking pictures or screenshots of the presentation and adding your notes to it.

Personal notes

- Five Whys Journal

- Morning Pages

- Gratitude Journal

- Five-Minute Check-In

- Mundane Things Enjoyed Journal

- Thanks, Learn and Connect Journal

- Bullet Journaling

- Drawing

- Correspond with Someone

- Daily Collage

- Journal from the Other's perspective

- Long-form "Classic" Journal

- One Line a Day Journal

- Dream Journal

- Vision Journal

- Core Values Journal

- Three Act Journal

- Atomic Journaling

- Interstitial Journaling

- Random Daily Journal Prompts in Obsidian

Personal notes are ones that you take for yourself. The typical example is maintaining a diary. I have a post that summarizes the benefits of a journaling habit which also lists a few famous people who are well known for having had a journaling habit or having been avid note takers. Read The Amazing Benefits of a Journaling Habit.

There are many ways to writing a diary. Here is an inventory of approaches I have come across.

Five Whys Journal

The concept of Five Whys comes from Lean Manufacturing practices. This is one of the powerful tools used for root cause analysis.

You start the process by writing down the problem that you are facing in your life currently to the top of the page. Describe your situation as clearly as possible.

Under your problem statement simply write the question "Why?" and then provide your response. When you are finished with your answer, repeat "Why?" under your response, and again articulate your explanation. Repeat the process of asking "Why?" five times, each time digging deeper and deeper to understand the root cause of the problem at the top of your page.

Morning Pages

The idea of Morning Pages was introduced by Julia Cameron. In summary, the concept is to clear mental clutter in the morning by writing three pages on whatever is on your mind. This is a stream of consciousness type of journaling approach, in which you simply write whatever pops into your head without editing. The approach helps clear the deck and get your mind ready for creative work.

An alternative to morning pages was suggested by Tim King. He calls his approach PAGES. The approach is like Julia's except that Tim recognizes the difficulty of finding time in the morning to write three pages of reflections. Also, he notes, our days are so busy, that by the time you get to do creative work, the effect of your morning mental cleanup might have already warned off. Tim recommends writing one to three pages right before you start your creative work - not necessarily in the morning and writing only as much as feels natural, not always pushing to get three pages.

Gratitude Journal

In a gratitude journal you respond to the same questions or prompts every day.

- My favorite thing about today was...

- I am thankful for...

- Today I noticed this [fill in the blank] about Mother Nature.

Using the same approach, you can play around with different prompts. For example, a check-in would look like this:

- How my feeling?

- Where am I feeling ease?

- What do I need right now?

It is helpful to go back and read through your responses occasionally. You might learn that certain people, places, or events trigger specific emotions.

Five-Minute Check-In

In the Five-Minute Check-In you record your thoughts and feelings, your musings, and observations. Speaking your check-in responses aloud can also be helpful, as that will make your reflection much more tangible for yourself. You may also consider recording these check-ins with your smartphone or dictating to a tool such as Otter.ai. Some suggest it is beneficial doing your check-ins roughly the same time each day.

Mundane Things Enjoyed Journal

This is a type of gratitude journal. Your objective is to reconstruct a moment as best as you can. The moment can be about anything, such as the awesome coffee you had in the morning, or the hot shower, or the slight breeze that hit you as you exited your home, etc. It is about putting to words those very simple things that you have experienced.

Thanks, Learn and Connect Journal

This is again, another type of gratitude journal. The more specific you are in your answers, the more value you will win through the process.

- What are you thankful for today?

- What have you learned today?

- What things and concepts have you made a mental connection for?

- With whom did you connect?

- What conversations did you have?

Bullet Journaling

Ryder Carol's Bullet Journaling stands on the borderline between journaling and productivity methods. It is a very lean approach to journaling.

Take a notebook. On the first page create an index page. Turn to the next page and on the top of the first spread, on both pages write the name of the month. On the left-hand side add the dates for each of the days in the month and the first letter of the day one under the other. This is going to be your calendar. On the right-hand side leave space for your tasks and to-dos for that month.

On the pages that follow, create a page for each day. This is where you will record tasks, events, and notes. Indicate a task by placing a small box in front of the task. Put “X” or a tick in the box when that task is complete. Use a dot at the beginning of the row to record some information or place a circle to record an event. When something is no longer relevant, just cross that line out.

At the end of the month, create the calendar for the next month. Flip through the pages of the previous month to cross off every unnecessary, or no-longer relevant action, and move the few that are still important to the to-dos of the next month by recording them on the right hand side of the monthly calendar page. This cleanup routine will help you regain focus.

Drawing

Draw your dream, your surroundings, your aspirations or worries.

Correspond with Someone

Instead of a journal, pair up with a friend and write regular updates. Share anything that you like. Respond to what the other person is sharing with you and thus create a dialogue.

Daily Collage

Create a daily collage to capture the essence of the day.

Journal from the Other's perspective

A remarkably interesting and educational technique is to write your journal from the Other's perspective. This is like writing as if someone else in your life was writing in their journal about you. Try to be as realistic as possible. This will help develop a healthy external perspective of yourself.

Long-form "Classic" Journal

Probably this is the first that comes to mind when you think about journaling. The Classic Journal includes long form paragraphs. This is very conscious writing and gives you the ultimate freedom to express yourself. This approach can also create a pressure to always write something meaningful. The Classic Journal also lacks structure that the other approaches on the list will provide.

One Line a Day Journal

On the exceptionally low end of the spectrum in terms of effort, the low barrier approach is the One Line a Day Journal. As suggested by the name, you are expected to write a single line each day, thus recording the core events of your life. This technique carries the risk of your daily journaling becoming very habitual and superficial.

Dream Journal

Dreams are where your creativity happens. Maintaining a Dream Journal will help you record your own creativity.

Vision Journal

Like vision statement of companies, you can have your own vision statement as well. In the Vision Journal you focus on clarifying your brand, your passion projects, your life purpose.

Core Values Journal

Identify three core values that you want to focus on for the next month or week. Each day write the heading for each of the values on the page. In your journal capture how you exemplified the specific value that day or how you need to work on your core values.

Three Act Journal

This is a creative way to spice up your journaling routine. Write the journal of your day as if you were writing a novel or short story. (I noted this down years ago, but I can't seem to find the source)

In Act 1 think about something that was pivotal, in your day. Something you were able to resolve or make significant progress on. Explain the context and the importance of it as if you were writing this as a story. Talk about the sequence of events leading up to the main event. Who were the main players? What were their possible motives? What were your motives? What conversations took place? What emotions were felt and by whom?

In Act 2 talk about what happened. What was the pivotal moment or the pivotal choice? How did it play out? What emotions were you feeling when the event occurred? Did it go your way or did it not? Did you handle yourself well or did you not?

Normally Act 3 is the falling action or resolution. This is where the reflection takes place. Use the third act to wrap things up and bring your mind from the conflict through the aftermath, to where you are now. Would you have done anything differently? What have you learned about yourself and about others? How will you approach similar situations in the future?

Atomic Journaling

I came across Atomic Journaling on Brandon Toner's blog. Brendon developed this method with Roam Research in mind. While Roam is an ideal platform to support his approach, it can be implemented using other notetaking tools as well.

In extremely simple terms, Brendon suggests creating collections of journaling prompts and implementing a daily routine to pick some of these for reflection. Over time you will build up a set of answers for each of the questions. You can circle back to your answers and look at how your thinking have evolved over time.

Further to Brandon's description of the Atomic Journaling, Andy Henson has a list of 191 journaling prompts to get you started. You can find Andy's prompts here. They are also available as a roam.json download.

Interstitial Journaling

I learned about Interstitial Journaling on Anne-Laure Le Cunff's blog. The method is originally attributed to Tony Stubblebine.

The process is simple. Make a short journal entry every time you take a break and record the exact time you took these. Having these written down will help you understand your own workflow, will give you an honest view about your productivity, as well as provide a fact-based record to help you reflect on distractions you experience during your workday. Recording your breaks will also help you become more self-aware about how you use your time.

Checklists

You are maybe surprised why checklists end up on a list of notetaking strategies. To be clear I am not talking about your shopping list or to-do list, even though those may include items you can "tick off". Checklists are tools to collect and reuse best practices in all sort of settings. Think of a "pack for holidays" checklist, a "project initiation" checklist, or a "publish a new post" checklist.

It is not by mistake that checklists are extensively used in aviation and increasingly in other complex fields such as medicine, construction, etc. Checklists are an ideal tool to aid you in complex activities and to help you learn from your mistakes.

I have two posts on the subject of checklists. The first one is my book summary of The Checklist Manifesto and the second one is a more hands on practical post about implementing a Checklist Habit.

Fleeting notes

Fleeting notes are quick, informal notes you take to capture an idea that pops into your head or that someone shares with you. They are meant to be temporary, to remind you of the idea or action you wanted to take.

Develop a robust inbox system - like the one recommended by David Allen in Getting Things Done, to ensure these notes get processed. Normally you will not want to create a filing system for fleeting notes, but rather you will want to process them and add the relevant actions to your action tracking or the thought to your permanent or evergreen notes.

What is your approach?

I'd like to grow this evergreen note into the definitive collection of notetaking approaches. I would be very interested in you note taking system. Please let me know what process or system you use. What your best practices are.

great content.. bookmarked. i have one doubt... what to do with number of tags which start increase in roamreseach?

ReplyDeletewhat you recommend for better tracking? do we need to make index page with all tags?

Hi Mahendra,

DeleteI am glad you found my post helpful!

That is an excellent question. I like it so much, that I will definitely write a dedicated post on the subject. I have a practice that I developed and used with TheBrain for many years. I am now migrating the approach to Roam... but of course the two systems have a different logic so the approach needs to be adopted.

In a nutshell I think index pages and evergreen notes are definitely part of the solution. As your question is Roam specific, then using namespaces is also very useful (i.e. #[[gtd/discussWith]] - you can format the tag in CSS to look nice on page). This will help you filter on the tag you are looking for.

Regardless of the notetaking system you use, I recommend creating multiple entry points into your notes. The more opportunities you have for finding something, the higher the likelihood that you will find it when you need it.

Finally you may also consider creating naming conventions. e.g. my tags start with a lower case letter, while my pages start with a Capital letter. A naming convention can go much beyond just the letter case. You can distinguish between topical tags, action tags, etc. By creating a CSS that works based on your naming convention, you will be gently reminded if you do not follow your naming convention, as your tag will look different then it should.

Just one more thing... if it's not too much of an ask... you could help others find this post by retweeting on twitter, or posting on Reddit, or other social media. I'd very much appreciate your help in getting the word out.

Thanks,

Zsolt