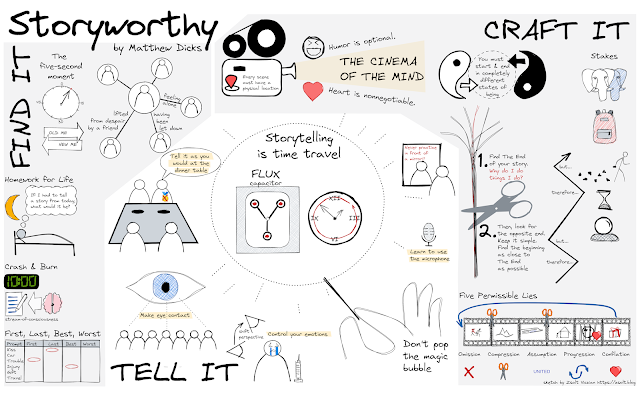

Storyworthy is a book by Matthew Dicks about the craft of telling stories.

This post is an experiment created over the course of three days. My ultimate goal was to create a single-page sketch note summary of Storyworthy. To achieve this, I first wrote a summary of the book using Tiago Forte's Progressive Summarization approach. I then created three one-page sketches for each of the main sections in the book. I finally distilled the three one-pagers into a single summary sketch - you'll find the single-page overview at the very end.

Introduction

- Finding stories to share.

- Crafting these to be engaging and entertaining with a long-lasting impact.

- Telling them to family, friends, or larger audiences.

When presenting at a meeting, conference, or training session, not only do you have an obligation to be entertaining, you have an opportunity to be entertaining. You have the chance to set yourself apart. Start with a hook and give people a reason to pay attention and remember your presentation. Attempt to be entertaining, engaging, thought-provoking, surprising, challenging, daring, and even shocking.

Finding Your Story

Stories are personal narratives that reflect change over time. At the heart of every story is a five-second moment in your life when something fundamentally changes forever. You can only tell other people's stories by telling your side of their story.

The purpose of telling a story is to connect with people. We've all felt alone, or have been let down by loved ones, and we have all had moments when we were unexpectedly lifted from pain or despair by the kindness of a friend. This is what people connect to.

Homework for Life

We all experience precious moments every day. These are often small things that we only notice if we pay attention. Homework for Life is a daily practice of spending five minutes at the end of each day answering the question:

”If I had to tell a story from today, what would it be?"

Write down your answer. Also, record any meaningful memories that came to mind over the day. Following this practice will ensure you have a wealth of stories to choose from.

In addition to Homework for Life, Matt shares two brainstorming techniques to help identify story-worthy material from your past.

Crash & Burn

Crash & Burn is stream-of-consciousness writing with the purpose to generate new ideas and resurrect old memories. Set a timer for ten minutes, launch the session by writing down a noun, an object in the room, then continue writing. There are only three simple rules.

- You must not get attached to any one idea.

- You must not judge any thought that appears in your mind. Simply write it down.

- You cannot allow the pen to stop moving. If your mind is blank start writing numbers, countries, colors, etc.

When you are finished review your writing to identify potential stories or anecdotes. Add those to your "master list" of stories.

First, Last, Best, Worst

First, Last, Best, Worst uses a table similar to the one below to guide the identification of potential stories. Prompts are listed to trigger memories. Combine prompts with the column headers to formulate questions such as "What was your first kiss?", "What was your last kiss?", "What was your best kiss?", and "What was your worst kiss?". Write your answers to each question in the cells of the table.

Prompt yourself by using objects in the room, a random page in a dictionary, or ideas you hear on the television or a podcast, etc. When finished review your answers. Do any entries appear more than once (the signal of a likely story)? Could you turn any of these into useful anecdotes or fully realized stories?

| Prompt | First | Last | Best | Worst |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kiss | ||||

| Car | ||||

| Trouble | ||||

| Injury | ||||

| Gift | ||||

| Travel |

Crafting Your Story

Finding the (frayed) ending of your story.

Stories are crafted to serve that singular five-second moment when something fundamentally changes for you, and only that moment. This moment must come as close to the end of your story as possible. Sometimes it will be the very last thing you say.

You need to very clearly understand your five-second moment. Ask yourself where your story ends. What is the meaning of your five-second moment? Why is it important? Say it aloud.

One way to discover the meaning of the moment is by telling your story. Speak it aloud. Don't worry about delivery and craftsmanship, just tell the story as honestly and completely as possible. Through this process, you will often discover (or rediscover) its meaning.

Another way of discovering the meaning of the moment is to ask yourself: "Why do I do the things I do?"

Stories can never be about two things. If through this process you find more than one meaning, you must make a choice which one your story is going to be about.

Finding your beginning.

You must begin and end your story in entirely different states of being. Once you know where your story ends, search for the opposite of your transformation, and this is where your story should start.

Search your past for the beginnings of your story. Don't latch onto the first thing that comes to mind. Make a list of possible beginnings and anecdotes, and analyze them for content, tone, the potential for humor, and connectivity to the story.

A written story is like a lake. Readers can step in and out of the water and control the speed at which the story is received. An oral story is like a river. It is a constantly flowing torrent of words. When listeners step outside of the river to ponder a detail, the river continues to flow. When they finally step back in, they will have difficulty catching up.

Strive for simplicity. Try to start your story as close to the end as possible. In storytelling, you should always try to say less. Shorter is better. Fewer words rule.

Try to start your story with forward movement whenever possible as that creates instant momentum in a story.

Never start your story by setting expectations such as "This is hilarious", or "You're not going to believe this". This will establish potentially unrealistic expectations. Also, starting with a thesis will reduce your chances of surprising your audience.

Five ways to keep your story compelling

Stakes are the reason audiences listen and continue to listen to a story. Stories that fail to hold your attention lack stakes. Stakes answer questions like: What does the storyteller want or need? What is at peril? What is the storyteller fighting for or against? What will happen next? How is this story going to turn out?

There are five strategies to infuse the story with stakes.

The Elephant

The Elephant is the thing that everyone in the room can see. It is a clear statement of the need, the want, the problem, the peril, or the mystery. The Elephant tells the audience what to expect and should ideally appear within the first minute, or even better if within the first thirty seconds.

One way to play with The Elephant is to present the audience with one Elephant, but then paint it another color. Make your audience think they are on one path, and then when they least expect it, show them that they have been on a different path all along. Don't switch Elephants. Simply change the color. This approach is especially effective when the end of your story is heavy, emotional, sorrowful, or heartrending. Keep the entire story from being filled with weight and emotion, by making the beginning light and fun.

Matt opening the story with meeting his friend while on Christmas shopping for his friends, and in desperate need for the love of "family & friends" prepares the story for the ending where his friends all gather around him in the hospital.

Backpacks

A Backpack is a strategy that increases the stakes of the story by increasing the audience’s anticipation about a coming event. It’s when a storyteller loads up the audience with all the storyteller’s hopes and fears in that moment before moving the story forward. This will make your audience wonder what will happen next. It will also help your audience experience the same emotion you have experienced in the moment about to be described.

Matt explaining how sitting in the car he was thinking about his desperation to get fuel and get home, and his strategy to negotiate with the clerk, allows his audience to enter the gas station with him.

Breadcrumbs

Breadcrumbs are when you hint at a future event but only reveal enough to keep the audience guessing. The trick is to choose the Breadcrumbs that create the most wonder in the minds of your audience without giving them enough to guess correctly.

In "Charity Thief" Matt drops a Breadcrumb when he says: But as I climb back into the car, I see my crumpled McDonald's uniform on the backseat, and I suddenly have an idea.

Hourglasses

Use Hourglasses when you are approaching the payoff. This is the time to slow things down by adding superfluous detail and summary. You may even reduce your volume as you approach the key sentence. Drag out the wait as long as possible.

In "Charity Thief" Matt uses Hourglasses after the Breadcrumbs, dragging out the story: An hour later, I'm standing on the porch of a small, red-brick house on a quiet, residential street. I'm knocking on a blue door. I'm wearing my McDonald's manager's uniform...

Crystal Balls

A Crystal Ball is a false prediction made by a storyteller to cause the audience to wonder if the prediction will prove to be true. We want people to know what we were thinking as well as what we were saying and doing. We spend our lives predicting the future and often these predictions are incorrect.

In "Charity Thief" Matt predicts that the man behind the blue door went into the house to call the police...

+1 Humor

Humor doesn't actually add to or raise the stakes of a story. It is a way of keeping your audience's attention through a section of your story that you think might be less than compelling. Humor is optional. Stakes are nonnegotiable.

Five Permissible Lies

Memory is a slippery thing. Research suggests that every time we tell a story, our memory of that story changes. No story is entirely true.

But you should never lie for your own personal gain, only for the benefit of your audience. Even then you must never add something that did not already exist in the moment.

Omission

If you were to share every detail, your story would never end. You need to make strategic choices on what to include and what to leave unsaid.

People are the most frequently omitted aspects to stories: third wheels and random strangers who distract audiences from the matter at hand.

Also, you have the choice of ending your story where you want, thus omitting endings that are undesirable. A story should be like a coat that is difficult to remove. Messy endings linger around longer. Omit the endings that offer neat little bows and happily-ever-afters.

When Matt tells his audience about the $604, he makes it easy for the audience to remove the coat.

Compression

Compression is to push time and space together in order to make the story easier to comprehend. Making a Monday-Friday story a Monday-Tuesday story. Compressing geography for sake of visualization. Compression removes needless complexity from the story.

Assumption

At times there is some detail that is so important to the story, that it must be stated with specificity. For example, to ensure, that everyone in the audience sees the same thing at the same time, but you can't actually remember the detail.

In the Superhero story, Matt did not actually remember the station wagon, he made the details up.

Progression

You may change the order of events to improve dramatic impact.

Like placing the Camden Yards scene to the end of the story, preceded by the strip club moment, to make people laugh before they cry.

Conflation

Use conflation to push all the emotion of an event into a single time frame, rather than describing change over a long period.

In "Bike off the roof" there were two days in between Matt talking to her sister and jumping off the roof, but in the story, it sounds better when told it happened the same day.

Cinema of the Mind

A great storyteller creates a movie in the minds of the audience. Unfortunately, however, often, instead of making the story the center of their performance, storytellers make themselves the center of the show.

Always provide a physical location for every moment of your story. If the audience can't see your story in their minds, the film is no longer running. Rather than stopping the story, for example, explaining a scientific principle, you could continue with a little anecdotal backstory that provides the necessary information and reveals something additional about your character. If there is a long stretch of backstory, remind the audience of the location halfway through.

I'm standing at the edge of my grandmother's garden, watching her...

But and Therefore

"And" is monotonous. The ideal connective tissue in any story are the words "but" and "therefore". These provide a zig-zag structure, these words signal change. The story was heading in one direction, but now it's heading in another.

Using this structure also helps craft your story as it provides direction and helps determine the next scene. Causation between each scene is what makes a story.

In a similar vein, saying what something or someone is not, is almost always better than saying what something or someone is. By saying what I am not, I am also saying what I could have been. Also powerful, are three sentences embracing the power of the negative, followed by a single, positive statement to summarize.

Heather laughed at me when (but) I wasn't trying to be funny. She refused my offer of a birthday cupcake, claiming she'd already had a cupcake that day, even though (but) it was only 9:30am. She chose to walk five miles home from school, even though (but) I offered her a ride and she lived next door to me. Heather despised me.

The secret of the Big Story: Make it little

"Big stories" are the hardest stories to tell. They are hard to tell because the big parts are often singular in nature. Unusual. Unique. They are hard for your audience to relate to, to understand.

Remember, the goal of storytelling is to connect with your audience. Storytelling is not about a roll-coaster ride of excitement. It is about bridging the gap between you and another person by creating a space of authenticity, vulnerability, and universal truth.

You must find the piece of the story that people can connect to. These are often little moments hidden inside big moments.

"This Is Going to Suck" is a story about friendship and love, not about Matt's head going through the windshield and dying on the side of the street.

Surprise

Surprise is the only way to elicit an emotional reaction from your audience. To make someone cry.

In "This Is Going to Suck" Matt paints the picture of a boy who is badly hurt and completely alone in a place where no one even knows his name. Audiences become emotional upon learning that Matt's friends have filled the waiting room outside the emergency room because this is also a surprise.

Avoid thesis statements

Thesis statements ruin the surprise every time. In storytelling, your job is to describe the action, dialogue, and thought. It is never your job to summarize these things.

Avoid opening sentences that summarize the moral of the story, and give away the surprise.

Heighten the contrast, increase the stakes

By putting a Backpack on your audience you can accentuate and enhance surprise. Use Breadcrumbs and Hourglass to highlight the surprise even further.

Hide important information

Hide the "bomb" in the clutter. Share superfluous details to hide one important piece of information that you'll use later in the story. You can also camouflage the bomb with a laugh. Laughter is an excellent way to hide something important that needs to surprise the audience later on.

Matt does this when he hides his all-important request for the nurse to call McDonald's into just another detail by placing it amid a series of doctor's and nurses' interactions.

Humor

Humor is optional. The heart is nonnegotiable.

We like to laugh. We want to laugh. But we listen to stories to be moved. Always end your story on the heart.

Timing

It is always good to get your audience to laugh in the first thirty seconds of a story. It signals to the audience that you are a good storyteller. It will put people at ease and make the next few minutes much easier.

In less formal situations, an early laugh is also a good STOP sign for potential interruptions. If they feel "intimidated" by your humor, people will be less likely to point out missing details or other elements that would ruin the flow of your story.

Later in your story humor is good to break the emotional intensity, to give people a break, to stop crying so they can feel something else. You can also use humor to increase contrast, by making your audience laugh before you make them cry.

Technique

Milk Cans and a Baseball

Milk Cans and a Baseball refers to the carnival game where metallic milk cans are stacked in a triangular formation and the player attempts to knock them down with a ball. In comedy, this is called setup and punch line.

"I was rescued from the streets by a family of Jehovah's Witnesses. I sleep in a pantry off their kitchen that they've converted into a tiny bedroom. I share this room with a Jehovah's Witness named Rick, a guy who speaks in tongues in his sleep, and the family's indoor pet goat."

Babies and Blenders

Babies and Blenders is the idea that when two things that rarely or never go together are pushed together, humor often results. One way to achieve this is to create a list of three descriptions, with the third being nothing like the other two. Another approach is through exaggeration, by pushing an unreasonable description against something that doesn't normally fit that description.

Charlie oozes love. But when it comes to food, my sweet, angelic, three-year-old boy is a little asshole.

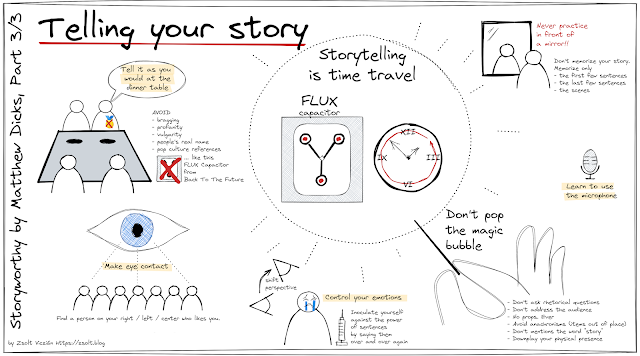

Telling Your Story

Stories should be told in simple language that does not sound "performancy". The way you would tell your story at the dinner table.

Never rehearse in front of a mirror!

The Present Tense is King

The present tense will bring you a little closer to the moments in time when the story is happening. It may even trick you into believing that you have time-traveled back in time to those moments. It creates a sense of immediacy.

Shifting to the past tense can signal a back story. By placing the backstory to the past you will avoid compromising the immediacy of the main story by bringing in a second present tense storyline.

The present tense will also help you see your story. You'll be able to connect to it more effectively, and your emotional state will more closely match your actual emotions from the time and place that you are describing.

"I'm writing this chapter on an Amtrak train from Washington, DC, to Hartford Connecticut. I'm sitting in the quiet car, but it's quiet nonetheless. The train rocks back and forth on the rails, dramatically increasing the frequency of typos...", and later switching to a backstory: " Two years ago, Charlie, Clara, and I were playing at a school playground on a hot summer day when Charlie announced that he had to pee…"

In a moment of heightened emotion or increased gravity, you will want to shift back to the present tense. This will also bring your audience “in the now”.

Telling a Hero Story

Avoid bragging. Success stories are hard stories to tell because failure is more engaging than success.

Summiting Mount Everest is an adventure story. Changing your life by summiting Mount Everest is a great story.

Malign yourself

People love underdog stories. Underdogs are supposed to lose, so when they manage to pull out an unexpected or unbelievable victory, our sense of joy is more intense than if that same underdog suffers crushing defeat.

Marginalize your accomplishment

People prefer stories of small steps over large leaps. Rather than telling a story of your full and complete accomplishment, tell the story of a small part of the success. Tell about a small step.

Time travel

Storytelling is time travel. Follow these rules to avoid popping the mystical time-traveling bubble.

- Don’t ask rhetorical questions.

- Don’t address the audience or acknowledge their existence whatsoever. If someone from the audience talks back, ignore it.

- No props. Ever. They never help.

- Avoid anachronisms. An anachronism is a thing that is set in a period other than that in which it exists.

- Don’t mention the word "story".

- Downplay your physical presence as much as possible.

Words to say, words to avoid

The words you chose will in part determine how your audience perceives you.

- Avoid profanity, though sometimes it might be appropriate to swear, such as when repeating a dialogue, when swearing is simply the best word possible, in moments of extreme emotion and for humor.

- Avoid vulgarity. Vulgarity is the description of events that are profane in nature.

- Avoid other people’s real names.

- Avoid pop culture references as it might backfire by risking alienating half of your audience, who might not be aware of the reference. If you compare a person to a celebrity, it will stick the celebrity into the story, and pops the mystical time-traveling bubble.

Performance

As long as the storyteller keeps telling a story, all is well.

- Don't memorize your story. Only memorize three parts to your story. The first few sentences - so you can start strong; the last few sentences - so you can end strong; and the scenes of your story.

- Make eye contact. Find a person on your left, a person on your right, and a person dead center who likes you.

- Control your emotions. As the moment of heightened emotion approaches in your story, press the “B” button. Shift your perspective from seeing your story through your eyes to seeing your story from above. You can also inoculate yourself against the power of certain sentences by saying them over and over again before performing.

- Learn to use the microphone. Find an expert and practice. Speak in a normal voice. Adjust the microphone perfectly before you speak. If given the option to use a microphone, do so.

Thirteen Rules for an Effective Commencement Address

- Don't compliment yourself.

- Be self-deprecating.

- Don't ask rhetorical questions.

- Offer one granular bit of wisdom.

- Don't cater any part of your speech to the parents

- Make your audience laugh.

- Speak as if you were speaking to friends.

- Emotion is good. Be enthusiastic. Hopeful. Even angry if needed.

- Don't describe the world the graduates will be entering.

- Don't define terms by quoting the dictionary.

- Don't use a quote that you've heard someone use. Instead, be quotable.

- End your speech in less than the allotted time.

Amikor Isten cselekszik

ReplyDeletePerzselő kánikula volt az elmúlt hetekben. Az ablakunk előtt hosszú ládákban virágzó bársonyvirág már délben lógatni kezdte fonnyadó leveleit, ha nem kapott elég vizet, de egy kancsó víztől mindig ismét életre kelt. A kertben virágzó rózsáknak is naponta kellet inni adnom, meg a gyepet is locsolni kellett. Sok száz litert ellocsoltam a drága ivóvízből (mert egy városi kertben mi más vízforrás lenne?).

Említhetném a gazdasági oldalát is, hiszen drágán mérik a vezetékes vizet – még ha külön mérőn is van a locsolóvíz, hogy legalább a csatornadíjat ne kelljen megfizetni érte. A munkaidőt nem is számolom, hiszen ugyan kinek számíthatnám fel!?

Nos, tehát sok munkával és költséggel mintegy 20x20 méteres területet sikerült megmentnem virágzó zölden. De ki gondoskodik a többi 93.000 négyzetkilométerről Magyarországon? Hiszen nem csak városi kertek vannak, és nem csak növényeket szerető nyugdíjasok, akik tudnak s akarnak idejükből, pénzükből erre szánni! Itt vannak a rétek és az erdők, a hatalmas mezőgazdaságilag művelt területek, de említhetném a közparkokat városon és falun egyaránt. Ki győzi mindezt vízzel?!

A meleget az ember is nehezen viselte, nem csak a növényzet. Éjszakára kinyitottunk minden ablakot, hogy amennyire lehet, átszellőzzön a lakás. Így tértünk nyugovóra a minap is. Éjfél után aztán arra ébredtünk, hogy röpül a lakásban minden ami mozdulni tud. A függöny természetellenesen vízsintes helyzetet vett fel, a menyezeti lámpa ingaóraként lengett, s a takarót is emelgette felettünk a huzat. Akcióba léptünk, s csuktuk sorban az ablakokat. Pont jókor végeztünk, mert egyszer csak „leszakadt az ég”, ömleni kezdett az eső, s én álltam az éjszaka közepén a fedett terasz ajtajában csodálva a villámok cikázását, az égzengést, a szakadó esőt, s a csodálat hangján szólítottam meg a teremtő és világot kormányzó mennyei Atyámat: „Uram, ez nem kispályás! Te nem kannából locsolod a földet! Hol van a mi kicsi erőlködésünk a Te hatalmas erődhöz képest? Még azt a kis vizet is, amit szétlocsolunk a kertünkben, Tőled kapjuk!”

Viczián Miklós

Thank you so much! I was actually looking for a review of this book, and you did a super job explaining what was in it. Really like your blog

ReplyDeleteThank you Zsolt! This is a great summary that I will keep using as a reminder. The book is also very good I recommend it.

ReplyDelete